HE'S NO ORDINARY JOE: JOE HENDERSON

Like his more celebrated contemporary, Wayne Shorter, Joe Henderson is a key element in the tenor saxophone chain, a link that connects hard boppers like Hank Mobley and Junior Cook with post-Coltrane avant-gardists like Pharaoh Sanders and Dewey Redman. He also was a pioneer in funk, electronic jazz, and fusion, yet never strayed far from his musical home, the hippest, cutting-edge jazz. Still for nearly three decades, awareness of Henderson's artistry barely advanced beyond fellow musicians and a narrow circle of discerning civilians. But after a string of Grammy-winning CDs and a slew of first-place poll finishes, Henderson, in his late fifties, began receiving, at long last, the wider acclaim he always deserved. In the wake of that sudden interest came the welcome release of two valuable boxed sets that document his prolific early years.

Like his more celebrated contemporary, Wayne Shorter, Joe Henderson is a key element in the tenor saxophone chain, a link that connects hard boppers like Hank Mobley and Junior Cook with post-Coltrane avant-gardists like Pharaoh Sanders and Dewey Redman. He also was a pioneer in funk, electronic jazz, and fusion, yet never strayed far from his musical home, the hippest, cutting-edge jazz. Still for nearly three decades, awareness of Henderson's artistry barely advanced beyond fellow musicians and a narrow circle of discerning civilians. But after a string of Grammy-winning CDs and a slew of first-place poll finishes, Henderson, in his late fifties, began receiving, at long last, the wider acclaim he always deserved. In the wake of that sudden interest came the welcome release of two valuable boxed sets that document his prolific early years.

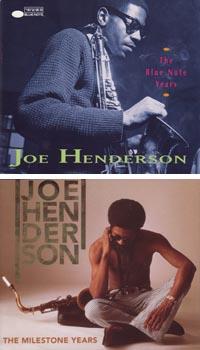

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, Blue Note produced more interesting, groundbreaking, and - thanks to master engineer Rudy Van Gelder - great sounding jazz than any other label in the business. Chronicling this artist's contribution to that output, Joe Henderson: The Blue Note Years (Blue Note CDP 89287, four CDs, total playing time: 4:38:17) is drawn primarily from the period 1963-69, during which the saxophonist appeared, either as a sideman or leader, on some thirty Blue Note albums. There also are a couple of tracks from his brief return to the label in 1985, and one off a 1990 date with pianist Renee Rosnes.

Henderson's seven Blue Note recordings (Page One, Our Thing, In 'N Out, Inner Urge, Mode for Joe, and The State of the Tenor, Volumes 1 & 2) are represented by ten of the thirty-six selections in this neatly packaged compilation. Included among these are the original recorded versions of two signature Henderson compositions, his bossa nova, "Recorda Me," and his Monk-inspired blues, "Isotope," as well as Kenny Dorham's "Blue Bossa," three tunes that, over the years, have become required playing for all aspiring jazz improvisors. The remainder of the collection features Henderson as a sideman, usually in all-star company.

Shortly before his twenty-sixth birthday Henderson made his recording debut on trumpeter Kenny Dorham's 1963 date, Una Mas. "São Paolo," a bossa nova from that session, demonstrates their common affinity for Latin genres. Dorham was one of the saxophonist's first boosters and they became close collaborators. Henderson also played on Dorham's 1965 album, Trompeta Toccata - for which he wrote the Latin-based "Mamacita," included in this set - Dorham appeared on Henderson's first three recordings, and for a time in the 1960s, they co-led a now legendary rehearsal band.

After premiering with Dorham, Henderson went on to record with the elite of Blue Note's huge stable of jazz talent. He adapted himself to a wide variety of forms, from the relentless hard bop of Lee Morgan (for example, "Gary's Notebook," culled from Morgan's The Sidewinder album) to the thoughtful modal jazz of pianist Andrew Hill, from Freddie Roach's traditional organ combo to Larry Young's Coltrane-influenced, cutting edge version. But no matter what he is playing or with whom, Henderson's unmistakable identity is ever-present.

In 1964, Henderson joined Horace Silver's quintet and appeared on the classic Song for My Father album, to which he contributed an up-tempo blues, "The Kicker," heard in this collection. The following year, he played on another Silver landmark, The Cape Verdean Blues, which was augmented on a handful of tracks (notably "Nutville," included here) by trombonist J.J. Johnson. That gig also began a long, fruitful partnership between Henderson and another Silver sideman, the personally erratic, although musically brilliant, trumpeter, Woody Shaw.

Besides Silver and the aforementioned Andrew Hill, Henderson can be heard here performing under the leadership of three other piano giants from the Blue Note roster, Duke Pearson, McCoy Tyner (who also appears on three of Henderson's dates), and Herbie Hancock. In 1969, while he was a member of Hancock's group, Henderson appeared on one of the seminal albums of the period, The Prisoner, whose title track is included here. Also worth noting are a pair of pretty ballads, "Sweet and Lovely," from a 1963 recording by trumpeter Blue Mitchell, and, off a date by drummer Pete LaRoca, a meditative, almost solemn, exploration of "Lazy Afternoon," a little-heard showtune that seems tailor-made for Henderson. Ernesto Lecuona's "Malagueña," from the same session, affords Henderson an extended opportunity to improvise over an undulating Afro-Cuban rhythm in 6/8 time.

The two LaRoca cuts also illustrate a central aspect of Henderson's art - the way he manipulates the sound of his saxophone to fit the character of a particular piece, while somehow always sounding like himself. For example, on "Lazy Afternoon" his tone is haunting, almost oboe-ish, and his vibrato is tightly controlled, while on "Malagueña" Henderson plays with a rich, deep sound and an expansive vibrato. This mastery of timbre becomes even more apparent in his later Milestone recordings, where, at various points, Henderson utilizes a whisper-soft subtone, a rough-edged, woody sound, various growls, rasps, and brays, and even a dark, bassoon-like nasality.

"Softly, as in a Morning Sunrise," from organist Larry Young's influential Unity album, demonstrates Henderson's command of chord changes and samples Woody Shaw's developing style. "Don't Get Sassy," recorded at a 1969 concert with the Thad Jones-Mel Lewis Jazz Orchestra, when Henderson was a regular member of the saxophone section, offers a rare taste of his work with the preeminent New York big band of the day. And two tracks from his live 1985 trio sessions, with Ron Carter on bass and Al Foster on drums, display the saxophonist's ease within a pianoless setting.

In 1967 Henderson moved from Blue Note to Milestone, where over the next eight years he released a total of twelve albums. All of these are included in full, along with a few unissued tracks and assorted loose items - a striking duet with alto saxophonist Lee Konitz on "You Don't Know Where Love Is," three fine tunes with cornetist Nat Adderley, and seven forgettable ones with singer Flora Purim - in Joe Henderson: The Milestone Years (Milestone MCD 4413, eight CDs, 9:46:09). This eye-opening collection documents where jazz was at from the late 1960s to the mid 1970s, and how the ever evolving and wide-ranging music of Joe Henderson helped it to get there.

Henderson's first Milestone recording, a sextet date titled The Kicker, is in a decidedly hard bop bag. Four of the tunes had been recorded previously by Henderson for Blue Note, but "Chelsea Bridge" gives him a chance to stretch out on a ballad, something he seldom did with that label. His sensitive rendering of the tune shows that Henderson had been an exceptional interpreter of Billy Strayhorn's music for at least twenty-five years before his Grammy-winning Lush Life disc. The sidemen are all first-rate, particularly trumpeter Mike Lawrence, a talented Henderson protégé who died of cancer in 1983, and the always reliable Kenny Barron on piano.

Tetragon is a quartet session (actually, two sessions), straight-ahead and late 1960s hip. Henderson's up-tempo jaunt through a reharmonized "I've Got You Under My Skin" is a delight, rivaling, perhaps surpassing, his similar treatment of another Cole Porter standard, "Night and Day," from the Blue Note Inner Urge. And as adept as he is at handling changes, Henderson is also not shy about playing "out." On "The Bead Game," he improvises freely and spontaneously over Don Friedman's piano punctuations, while Ron Carter and drummer Jack DeJohnette lay down a restless pulse. It may be free, but it swings like mad.

Herbie Hancock, with whom Henderson was working at the time, plays piano and electric piano on 1969's Power to the People. The music, like the album's title, is aggressive and forthright, but Henderson also reveals an introspective side on his delicate composition in 3/4 time, "Black Narcissus." "Lazy Afternoon" gets a medium-swing treatment here, entirely different from the LaRoca-Blue Note version, and "Foresight and Afterthought" offers spontaneous trio interplay among Henderson, Carter, and DeJohnette.

Recorded at the Lighthouse in 1970, If You're Not Part of the Solution, You're Part of the Problem, introduces Henderson's working quintet of time, with trumpeter Woody Shaw in peak form. Both the album's title and George Cables' electric piano were signs of the times. Henderson and company perform their typical nightclub set: updated, on-the-edge versions of his Blue Note repertoire along with a stunning "'Round Midnight," played first in a rubato duet with Cables - who is plagued by some momentary distortion from his keyboard - then in breathtaking double time, and back to rubato for the coda. But there is a new wrinkle here. The title track represents Henderson's first foray into what Bill Kirchner, whose insightful liner notes have been illuminating quite a few major reissue projects lately, calls "his personal brand of thinking man's funk." This would remain an important element of the saxophonist's musical output for the rest of his Milestone years.

In Pursuit of Blackness is a mixed bag, with two leftover numbers from the Lighthouse sessions and three by Henderson's new sextet. On "Mind Over Matter," Henderson's tenor saxophone wails and moans convincingly while Pete Yellin's bass clarinet and flute add texture and color. However, trombonist Curtis Fuller is unusually subdued here, seemingly at sea in this Bitches Brew-inspired current. Fuller is much more at home on "No Me Esqueca" (a retitled "Recorda Me") and "A Shade of Jade," the kind of material that he really can sink his hard bop teeth into.

Black is the Color, from 1972, recalls that brief moment when fusion was still a viable and creative musical form, instead of the empty and excessive commercial formula into which it soon would degenerate. The session features extensive guitar, keyboard, synthesizer, and percussion overdubs, and Henderson himself plays multiple horn tracks on one tune. Still, "Vis-a-Vis," performed by an unencumbered quartet of Henderson, Cables, DeJohnette, and bassist Dave Holland, testifies that the saxophonist had not abandoned the more familiar aspects of his music, but was using his taste, intelligence, and deep mainstream roots to nourish his work in this new realm.

A word should be said about the titles of many of Henderson's Milestone recordings. These days, snide, small-minded, would-be pundits are quick to dismiss such unabashed expressions of social consciousness as Power to the People or Black Is the Color with that now-current epithet: "PC." That sort of smug cynicism slanders the seriousness and sincerity with which concerned artists like Henderson used their work to address burning, and still unresolved, social questions. Having named his recordings and compositions in this way, Henderson stood up, spoke up, and challenged people to think beyond mere musical notes to essential extra-musical questions. And so, for seeking to lift jazz beyond the realm of mere entertainment, Henderson and his contemporaries merit praise and gratitude, not derision.

Henderson is accompanied by a surprisingly solid Japanese rhythm section on one his finest dates ever, the live Joe Henderson in Japan. His treatment of "'Round Midnight" differs markedly from the Lighthouse version, boldly opening with a dramatic, unaccompanied chorus, followed by straight ballad tempo that moves seamlessly into a comfortable, but never complacent, double-time groove, and closing with an unaccompanied coda. Dorham's "Blue Bossa" is always welcome, "Out 'n' In" is a fast, free-flowing blues in the "Chasin' the Trane" mold, and "Junk Blues" is more than an exercise in modal improvisation. It's a virtual textbook.

Henderson's next release, Multiple, resumes and refines his experiments with fusion and overdubbing. The technical devices are employed in a more concise, less obtrusive way than on Black Is the Color. The compositions are not only compelling and evocative (Henderson's "Song for Sinners"), but even pretty (DeJohnette's "Bwaata").

A concept album from 1973, The Elements consists of four tracks depicting the basic elements of ancient mythology: "Air," "Water," "Fire," and "Earth." Luckily, Henderson, whose compositions reveal deep African roots, was able to undertake this fascinating project before the New Age zombies claimed and blighted the territory. Michael White's violin is romantic and melancholy, and bassist Charlie Haden, with his full sound and rich tone, is integral to the mix. The biggest surprise is Alice Coltrane, the Yoko Ono of jazz, whose contributions on piano, harp, tamboura, and harmonium surpass anything she did on her late husband's recordings.

Latin music always had been a favorite idiom for Henderson, but Canyon Lady, also from 1973, was his first completely Latin-flavored recording. The ensembles, arranged by trumpeter Luis Gasca, provide dense settings for Henderson's tenor, particularly on "Tres Palabras," on which Gasca employed two trumpets, two trombones, three flutes, piano, electric piano, bass, drums, congas, and timbales. For contrast, there is a previously unreleased gem from these sessions, "In the Beginning, There Was Africa ...," a free improvisation by Henderson, accompanied by only conga drums and timbales.

Black Miracle, recorded in 1975, was an attempt to produce a funk-driven hit album. It didn't sell, most likely because Henderson didn't sell out. Purists may turn up their noses at Ron Carter's Fender bass and George Duke's electronic keyboards and synthesizer, but there's no compromise in Henderson's searing tone, moaning vibrato, and multiphonic cries. And his straightforward rendering of Stevie Wonder's "My Cherie Amour" reflects the sound belief that good pop tunes deserve to be taken seriously.

German pianist Joachim Kühn, a McCoy Tyner disciple and Henderson discovery, is featured on Black Narcissus, the saxophonist's final Milestone release. Most of the tracks are fattened with a synthesized "string section." The non-synthesized blues, "The Other Side of Right," indicates that they might have been better off without it. Still, even this least distinguished segment of Henderson's vast output has much to recommend it, notably his poignant reading of "Good Morning, Heartache" and "Amoeba," on which he overdubs two improvised saxophone parts (and synthesized bass) backed by drums and percussion.

It was a common, and all too true, complaint about the "young lions"-dominated jazz scene of the 1980 and '90s: to get noticed it seemed as if you either had to be eighteen years old or eighty. Musicianship was at best an afterthought and at worst irrelevant. Joe Henderson proved to be an exception. Success and acclaim found him at a time in his life when he was mature enough to handle them and still vigorous enough to enjoy them. But sadly, his time in the sun was much too brief. In 1998 a debilitating stroke forced him to give up playing publicly, and on June 30, 2001, Joe Henderson died at the age of sixty-four.

© Bob Bernotas, 1995; revised 2008. All rights reserved. This article may not be reprinted without the author's permission.