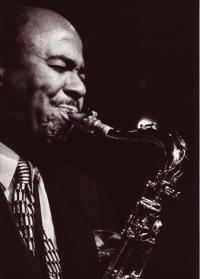

MOVING EVER FORWARD: BENNY GOLSON

Benny Golson is a serious man who doesn't take himself too seriously. A born storyteller, he possesses a philosophical bent and a refreshing, self-deflating sense of humor. Sitting in his comfortable, carefully furnished Upper West Side apartment, he discussed his accomplishments with a combination of rightful pride and genuine modesty.

Benny Golson is a serious man who doesn't take himself too seriously. A born storyteller, he possesses a philosophical bent and a refreshing, self-deflating sense of humor. Sitting in his comfortable, carefully furnished Upper West Side apartment, he discussed his accomplishments with a combination of rightful pride and genuine modesty.

Born in Philadelphia on January 25, 1929, Golson first played the piano, but he gave it up when he found his true love, the saxophone. It's a story he enjoys telling, and he does it in vivid detail. "When I reached fourteen," Golson begins the tale, "I went to the theater in Philadelphia and I heard Lionel Hampton's band, and I heard a fellow named Arnett Cobb. He stepped out to the microphone and played that famous tenor solo on 'Flyin' Home' [originated by Illinois Jacquet]. And though Earl Bostic was in the band and playing a 'bag of snakes' [on alto], somehow it was Arnett's playing that fascinated me. I guess it was more gutsy, or whatever, whereas Earl Bostic was very sophisticated, and my mind wasn't ready for that.

"But anyway, after that I was drawn to the tenor saxophone, not even knowing that it was the tenor saxophone. I just described it as 'the saxophone with the curve in the neck.' My parents weren't able to get me one at that time. They were not well-to-do, and we were struggling as it was. And so I took to listening to the radio when I finished my homework - that was long before television - and I would find myself listening to all these sounds, no matter what they were, waiting to hear the saxophone solo. It didn't matter to me at that time that I didn't know what I was listening to - whether it was alto or tenor. I would wait and listen for the saxophone solos, and I just became fascinated by it. You know, in those days it wasn't chorus after chorus. It was the days of the three-minute recordings, so the saxophone solo was eight bars or sometimes only four bars. But to me, it was just so outstanding, it was so important.

"Then one day, a hot summer's day, I was sitting on the step. It was just about time for my mother to come home from work, but she was later than usual and I was wondering if anything had happened. Finally, she made the turn at the corner after leaving the streetcar and I noticed she had this suitcase, I thought, in her hand. But as she turned sideways I could see it was elongated, and my heart jumped. I thought, 'No, this can't be. No, this is something else,' because I knew we didn't have the money. But during those days you could put a dollar down and pay a dollar a week - forever - and she did something like that.

"As she got closer she began to smile, and she called to me, a few doors down, 'I've got something for my baby!' And then I knew - I almost exploded with joy. She said, 'I've got a saxophone for you!' Words are anemic to try to describe my elation. I was overwhelmed completely. I was possessed."

But getting started was not quite as easy as the eager youngster had thought. "We took the horn inside," Golson continues, "and laid it on the couch and opened it up - a beautiful, two-tone gold and silver Martin saxophone, which was a first-rate saxophone, as it turned out. As I looked at this beautiful thing in front of me I suddenly became depressed, because I realized that I didn't even know how to put it together. I thought once you opened it, you were ready to play. Not so. You had to the put the reed onto the mouthpiece, affix it with the ligature, put the mouthpiece onto the neck, and put it all onto the horn.

"Well, I didn't know about that. And so I was confused, I was frustrated, and yet enthusiastic all at the same time. So my mother said, in her wisdom, 'Let's go around to Tony Mitchell's house.' Tony had been taking saxophone lessons for three or four years. We walked from our house around to his place and, sure enough, he was there, and we went in. He saw that I had a new horn. 'Oh, this is fantastic!' He says, 'Do you know how to play it?' Of course I didn't. So he says, 'Do you know how to put it together?' And of course I didn't. So he took it out and put it together for me, and as he did, he showed me what each piece was for and how it fit together.

"So we put it together and he says, 'Do you want me to play something?' I said, 'Yes!' He put my neck strap on and attached the saxophone and started to play Ben Webster's solo on - I'll never forget it - 'Rain Check.' When I heard this thing being played solo in front of me, live, it was so special that I was even more overwhelmed. After he played a few other things he took it off and put the strap around my neck, and he says, 'Now you try it.' And then I was more depressed than ever. It sounded like a mule who had been mortally stabbed in the heart. That sound that I was getting out of this instrument, it was just terrible. You know, I didn't know anything about it.

"So we decided I needed a teacher, and I got one that was pretty good. This fellow had been with Charlie Barnet's band and decided that he wanted to settle back down in Philadelphia and spend some time with his family. But in those early days when all this happened, it was summertime, and in my neighborhood all the windows were open. So when I would practice the whole neighborhood knew it. And I guess everyone hated me because I was playing this thing very badly all day long. When night came and I went to bed, everybody breathed a sigh of relief. But it eventually got better. After four months I had my first gig."

The Philadelphia of Benny Golson's youth was loaded with developing jazz talent, like saxophonist Jimmy Heath, pianist Ray Bryant, and drummer Philly Joe Jones. There was another young saxophonist, transplanted from North Carolina, whom Golson met while he was still in high school, and the memory of that old friend propels him into another wonderful story. "There was a fellow named Howard Cunningham that played alto," Golson remembers. "We went to high school together - Ben Franklin High - and he told me one day, 'There's a fellow that just moved into the projects that plays saxophone.' I said, 'What does he play? Tenor?' He said, 'No, he plays alto, and he plays just like Johnny Hodges.' When I heard that, I said, 'Really? Just like Johnny Hodges?' He said, 'Maybe I'll bring him by the house one day next week.' I said, 'Bring him by.'

"Sure enough, one afternoon the following week after school, my doorbell rang and there was Howard and this stranger with an alto saxophone case in his hand. They came in and Howard said, 'This is John Coltrane,' and I was thinking to myself, 'That's a very strange name,' 'cause right away I was thinking about 'freight car, box car, coal train.' We used to call him those names, in jest, and he took it very well.

"I'll tell you, kids are something. I must have been about sixteen, and I said to him, 'Play something for me,' as though I were the authority. Innocent ignorance, I guess. And he whipped his horn out in a flash and started to play 'On the Sunny Side of the Street' just like Johnny Hodges. And my mother, who was upstairs, said, 'Who is that down there?' I said, 'Oh, a fellow named John Coltrane.' Every time we had a session at my house thereafter, she would holler downstairs and say, 'Is John down there?' And he would say, 'Yes, Mrs. Golson.' Before we got started, he had to play 'On the Sunny Side of the Street.' "

Golson and Coltrane became fast friends. Then, on the unforgettable night of June 5, 1945, bebop invaded Philadelphia. Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker performed in an all-star concert at the city's Academy of Music, and the two aspiring saxophonists, along with Ray Bryant, were in the audience. They were never the same. "We almost fell over the balcony," Golson laughs, "because this music was so new there was no precedent for it. We were trying to come out of the other kind of music, you know, Jimmie Lunceford and 'Flyin' Home' à la Lionel Hampton and 'A Train' by Duke Ellington. We heard this music - I mean, our lives were changed. And so we had to get about the business of finding what it was all about.

"We were hearing somebody play something that we'd never, ever heard any day that we'd been on this earth. It was epochal. At that point our lives did change, and it became even more exciting for us. It was exciting before, it was all an adventure, but it became more exciting to us then. We had something that we wanted like we wanted life's breath.

"After that concert was over, we went backstage, like kids do, and got everybody's autograph. It was an evening concert, and Charlie Parker was going over for the first show at a place called the Downbeat. And so John and I were walking up Broad Street with him, and John was saying, 'Can I carry your horn for you, Mr. Parker?' I'm on the other side saying, 'What kind of mouthpiece do you use? What kind of reeds do you use? What strength reed do you use? What is the make of your horn?' This crazy kid stuff, and he was telling it all, and I thought I was getting the real lowdown.

"We got to the club - of course, we were too young to go in - and he said, 'Kids, keep up the good work,' and he went upstairs. We spent the night just standing out front listening to them play from up on the second floor, and walked home talking about it after it was over. This was exciting stuff to us, you have to believe that."

With the memory of that concert indelibly etched in their brains, Golson and his friends began to explore this exciting new territory. "It was a slow process," he looks back, "because we were breaking new ground. Dizzy and Bird were breaking new ground themselves, of course - they were way out front. But we were trying, as kids, to find out what it was all about, and we had nothing to draw upon other than the recordings. We lived with those records.

"So it was the empirical process, learning by experience, syllogistic reasoning, that deductive thing where, if this doesn't work, that doesn't work. Or this works and that works - well, this is related to it, then this will work. We had to go through trial and error. That was slow and laborious, but wonderfully laborious because we enjoyed every minute of it."

By the following year, Coltrane - now playing tenor - had progressed enough to go on the road with alto saxophonist-singer Eddie "Cleanhead" Vinson's R&B group, while his buddy remained in Philadelphia. A year later Coltrane was back in town (and back on alto) when he and Golson played in Jimmy Heath's highly regarded local big band. "Jimmy was a little ahead of the rest of us," Golson recalls. "He had quite a mind for jazz and the new movement. He adapted to it right away and he was moving ahead."

After high school Golson enrolled in Howard University in Washington, D.C. "I could not enter the school of music on the saxophone. They wouldn't accept it. I had to enter on the clarinet. I was a nighttime saxophone player. During the day I had to practice my clarinet, but when the sun went down, I'd go to the laundry room in the basement of the dormitory and play my saxophone. So whatever I learned on the clarinet, I transferred to the saxophone. But it had a great, boomy sound down there. It made me sound bigger than I was."

Howard's music program was, to say the least, conservative. Twentieth-century classical music was heresy. Even worse, Golson recalls with bemusement, "We could be expelled for playing jazz on the school premises." He was majoring in music education and began to minor in rebellion.

"We had lots of rules that we had to follow in the theory of composition. When I would do my homework, my heart wanted to go in other directions, which would break the rules. In the music composition and theory class we got a cantus firmus one day, and I harmonized that thing following my heart. We went to class that next day, and the professor was in the habit of examining the homework at the piano in front of the class. She was going over each person's work. 'Ahhh, Miss Bryant, this is good, very nice. Mr. Brown, oh, very nice here.'

"And then she got to mine. At the first chord, I saw a frown on her face and she took the red pencil - slash! She went to the next chord and she looked with some consternation at the paper. The red pencil went slash again. She went on playing, and after a while the red pencil was slashing like Zorro's sword. Finally she saw there was no need to go to the end. She turned to me and said" - he speaks slowly, elongating every word - " 'Mr. Golson, what have you done?' I stood up like I was making a proclamation and boldly said, 'That's the way I heard it!' Of course, that didn't go over too well."

Discouraged and disenchanted, Golson considered taking some time off and then transferring to the Boston Conservatory. "They were one step away from throwing me out anyway," he admits. "But I started to work - I left in my junior year - and I never got back. I've been fortunate enough to be working ever since." His first job after he left Howard in 1951 was with guitarist Tiny Grimes. "He used to play with [pianist] Art Tatum," Golson explains. "Art Tatum was able to play anything he knew in any key." Grimes learned that skill from Tatum and he expected it from his sidemen.

"We played the same tunes every night," Golson notes, "but we never knew what key we were going to play them in. He would give us a little introduction so we could determine the key and be ready to play. Some nights I'd hear the piano player say, 'Oh, no!' But whatever it was, we had to play it in that key. It was kind of rough sometimes, stumbling around a little bit, but after a while you got used to it."

After Grimes, Golson joined singer-saxophonist Bull Moose Jackson's R&B group, where he met pianist-composer Tadd Dameron. He started writing for the band, with Dameron's help. "I picked Tadd's brain completely apart, and he let me do it. He was very friendly, quite open, with me. I learned quite a bit from him." After a short stay with Lionel Hampton's big band, Golson took John Coltrane's place in Earl Bostic's combo.

"This guy was a virtuoso on the saxophone," Golson says with awe as he recalls Bostic's skill. "I don't think there was anything he didn't know about the saxophone. Tremendous knowledge. He could start from the bottom of the horn and skip over notes, voicing it up the horn like a guitar would. He had circular breathing going before I even knew what circular breathing was - we're talking about the early '50s. He had innumerable ways of playing one particular note. He could double tongue, triple tongue. It was incredible what he could do, and he helped me out by showing me many technical things."

But by 1956 Golson had become restless with Bostic's commercially oriented music. "That's the only band I ever got fired from," he admits, laughing. "I got tired of playing that music. Although I was making a living, I wanted to do other things. "When we'd go down South, he pull out his guitar - people don't realize that he played guitar, after a fashion - and he would play those kinds of songs that the people like in the South. It used to bug me so much. Sometimes, during the intermission, I would de-tune the guitar - tighten one string, loosen another one. When he'd call off a tune, he'd just pick it up, kick it off, and get ready to play, and of course, it would just sound awful. He couldn't figure out what was happening until he saw me do it one night, and he said, 'Look, don't touch my guitar.'

"I was so beside myself," Golson continues. "Once I saw Illinois Jacquet, in one of his performances, had the crowd going so with what he was playing that he moved back by the drummer, ran out to the edge of the stage, took off his strap, drew the horn back, and gave a throwing motion like he was going to let it go into the audience. Everybody ducked and then laughed. They just thought it was great.

"So one night while Earl was playing, I guess, like Flip Wilson used to say, 'The devil made me do it.' I ran back to the drums and ran toward the front of the stage, drew my horn back like I was going to throw it, and made a throwing motion and everybody ducked. Off course, all the attention was on me and not on Earl - he was right in the middle of a solo. When he finished playing, oh, he was livid. He said, 'Look, Podno' - he used to call everybody not 'Partner,' but 'Podno' - 'you can do all of that kind of stuff on your solo, but when I'm playing, don't do it on my solo!' But it was just getting worse, so the next night he said, 'Podno, I think I'm gonna have to let you go.' So he gave me my fare and sent me back from Seattle, Washington."

But the firing turned out to be a big break for Golson. Shortly after he got back home he was hired into Dizzy Gillespie's big band on a recommendation from Quincy Jones, who had met Golson during the saxophonist's brief stay with Lionel Hampton's band. "I joined Dizzy without any rehearsal at the Howard Theater in Washington, D.C.," Golson recounts. "And even though I'd heard him on the records and knew what he could do, knew what his ability was and knew his stature, it's something else sitting there first hand, being a part of what he's put together and listening to him play just about five feet in front of you, standing in the spotlight. It was awe inspiring.

"After that particular show was over, I felt compelled to say something to this man, but I was embarrassed. I didn't quite know what to say. All I could say as we walked offstage into the wings - we both laughed at it when I recalled it to him years later - was, 'Dizzy, wow, you sure were playing!' " Pondering his youthful exuberance, Golson lets out a hearty laugh. "I could see that he was embarrassed, too, with the fawning, and he said, 'Aw shucks, I wasn't playin' nothin'.' So we were both standing there embarrassed. He had that much humility, which kept him moving ahead always. He always had more to do. He wasn't satisfied. He had not, in his own mind, arrived."

When Gillespie's band broke up in 1958, Golson decided to stay in New York and establish himself as a writer. One night, after a month or two of occasional record dates and commercials, Art Blakey called and asked him to come down to the Café Bohemia and sub with his Jazz Messengers. Golson eagerly agreed. "I don't remember what he paid me. He didn't know, but I would have played for free."

At the end of the night Blakey told Golson that he would need him again tomorrow, and the saxophonist obliged. After that second night the crafty Blakey asked him to finish out the week. "Art was a very slick fellow," Golson observes, "and without my knowing it, Art was sucking me in. When the week was over, he said, 'Look, you played with us this week. I know that you want to stay in New York, but I really don't have anybody yet and you know the music now. Do you think you could go to Pittsburgh with me? Just one week. That's all I've got - one week.'

"And I'm really loving the music, so I said, 'Yeah, I can go with you.' At the end of that week in Pittsburgh, he said, 'Look, I hate to tell you this, but before we go back we've got one week in Washington, D.C. You think you could help me out, 'cause I really don't know who I'm gonna get?' And I said, 'Yeah, OK. All right.' And I thought, 'Oh God, I'm dead.' We went there and played, and after that I never said anything else about staying in New York. I just went on to the next gig. He had me."

Golson began to counsel Blakey on a wide range of matters, business related as well as musical. "He had such tremendous talent and he wasn't making much money. I happened to say to him one night, 'You know, Art, it's a shame. You should be a millionaire.' He says, 'Yeah, I know. What's wrong?' I'm the new guy in town, talking to him like I really know what it's all about. I said, 'Art, I see some things that really need changing.' He says, 'Like what?' I said, 'Well, Art, you need a new band. 'This is incredible - I don't believe I said this! He said, 'Really?' and he was looking at me with those big, sad cow eyes."

And so Golson advised Blakey to fire his band - "the audacity," he muses, still astonished, "the temerity of me" - and rebuild it with three up-and-coming Philadelphia musicians: pianist Bobby Timmons, bassist Jymie Merritt, and a twenty-year-old trumpet sensation whom he had met in Gillespie's band, Lee Morgan. He arranged a Town Hall concert and a European tour, and beefed up the Messengers' book with original tunes like "Along Came Betty," "Are You Real," and "Blues March." Golson also cajoled Timmons into expanding a funky little lick into what would become one of the signature tunes of hard bop.

"Bobby Timmons on the gigs, in between tunes, he had this eight-bar thing he used to play. He would play it, and we'd always say, 'Oooh, that's funky.' And we never thought anything about it. But I starting thinking about it, that funk thing that he used to play. When we got to a place called Marty's in Columbus, Ohio, I called a rehearsal and I guess they were wondering why, because we had memorized everything. 'So, what are we going to rehearse?' I said, 'Trust me.' I used to always say that, like I was some authority.

"So we went to the club the next day and I said, 'Bobby, remember that little thing you play in between the tunes when you're on the bandstand, and we all laugh because it's so funky? What we're gonna do, we're gonna use that eight bars with another eight bars, and while we're here I want you to write a bridge to it.' He said, 'Oh, that's nothing but just a little lick.' I said, 'Believe me, I think there's something there. We're going to go over here and sit down and lollygag, and you go on the bandstand and you write a bridge for it.'

"So in about fifteen or twenty minutes he says, 'OK, I got it.' He played it, and I said, 'Bobby, no, you missed it. You've got to get the same feeling on the bridge that you have on the part that precedes it.' He said, 'Well, you write it.' I said, 'No, it's got to be you. I'm going to sit down again, and you come up with something else.'

"And he did. I said, 'OK, Bobby, that sounds good.' And Lee and I learned it. Lee and I, for some reason, had the extraordinary ability to play and think and breathe exactly the same. And we never practiced it. I wasn't aware of it myself 'til somebody pointed it out. We played exactly as one. I said, 'OK, we've got it down. Now we're gonna play it tonight, and I'm going to pay particular attention to the audience and see what it does to them.' We played it and laid them out. Boy, they loved it. The name of the tune was 'Moanin'.' "

In October 1958, when Art Blakey's Jazz Messengers recorded "Moanin' " for the classic Blue Note album of the same name, Golson achieved one of his most striking feats as an improvisor. As Lee Morgan concluded his solo, he tacked on a brief seven-note phrase, almost as an afterthought. Without missing a beat, Golson leaped into his first chorus by repeating that phrase. "It just happened on that particular take," he recalls. "It just hit me that way. It sounded so good, and it's from a rhythm and blues song that I grew up with: 'I want a big fat mamma.' "

Golson proceeded to work with the phrase, transposing, elongating, and inverting it, and ultimately creating a fully realized, thirty-two-bar chorus of out Morgan's original seven notes. It's an illuminating illustration of the compositional resources that the finest jazz improvisors draw upon - in particular, their ability to develop thematic material spontaneously and coherently. "Improvisors are composers." Golson agrees. "Rather than transferring their thoughts to pencil and paper, they transfer their thoughts from their mind to their instrument. But it's composition, it really is - of a different kind, of course."

After about a year with Blakey, Golson recalls, "I got restless again. I realized that I had deviated from my plan, where I wanted to do something to forward my career. So I told him, now that he was really in good stead, just to keep going in that same direction. I was going to leave, but if there was ever anything I could do for him, if there was anything he wanted to ask me, don't ever hesitate. Years after that he called many times and asked me what did I think about this, did I think he should do that?"

Planning to form his own sextet, Golson had hoped to hire, as his trumpet player, an ex-Lionel Hampton colleague, Art Farmer. Ironically, he discovered that Farmer was preparing to leave Gerry Mulligan's quartet and had a similar idea of his own. "When I called him first and told him, he started to laugh," Golson recounts, "because he says, 'You know, that's really something. I was thinking of putting together a sextet and calling you.' "

"We had worked on various projects together by that time, and Benny and I had always gotten along very well. I had the idea for him to work for me," Farmer confirms with a chuckle, "and he had the idea for me to work for him." They decided to make it a co-leadership and called their new group "the Jazztet." The brilliant trombonist Curtis Fuller joined Golson and Farmer in the Jazztet's front line, and on piano they hired a twenty-year-old Philadelphian, McCoy Tyner. The pianist still was living in his hometown at the time, so the co-leaders found an apartment in New York for him and his wife. Tyner enlisted someone to drive him to the city and was on his way when, Golson recounts, "I got a call. 'We broke down on the New Jersey Turnpike. Can you come out and pick me up?'

" 'McCoy, I don't have a car. What am I gonna do?' Then I said, 'Wait a minute' - he gave me the phone number of where he was - 'I'll call you back.' I called John Coltrane, who had a car. John came out to our house, and we went out and picked McCoy up and brought him in. A little later, you know, he left us and joined John's quartet. I said to John, 'Fine friend you are. I went out and picked up a piano player to join our group and you stole him!' We laughed about that for years."

Farmer and Golson kept their group together until 1962, when personnel changes and fewer gigs made it, in Farmer's words, "too cumbersome." (They did revive the Jazztet for a period during the 1980s.) Soon Golson's restless nature began drawing him into an entirely new realm. Friends like Quincy Jones and Oliver Nelson were making good livings in Hollywood, writing for films and TV. They encouraged Golson to join them. He was interested, but first he prepared. He studied advanced composing and orchestrating techniques, went to Europe and scored a profoundly forgettable film, returned to the States, and studied some more. By 1967 Golson felt ready for Hollywood.

"Through Quincy," he says gratefully, "I went to work right away at Universal Studios. Then Twentieth Century [Fox] picked me up, and I started to do some work over at Columbia right away." Working primarily in television, Golson was composing music for hit series like It Takes a Thief, Mission Impossible, Mannix, M*A*S*H, The Mod Squad - "I can't even remember all the shows" - and innumerable commercials for TV and radio.

While building a successful writing career, Golson's saxophone playing suffered. Actually, it disappeared. "I put the horn down when I went out there," he explains. "I would not take any jobs playing. I said, 'My playing days are over. I don't want to be known as a bebopper because I want to write dramatic music.' So people stopped calling me." For almost eight years, he never took his horn out of the case, "even to look at it."

But by the early 1970s the old urge returned. "I was beginning to get restless. I felt like I wanted to play the horn again. I picked the thing up, and it felt like a piece of plumbing, like I'd never played it before. I had no chops. I had no endurance. My concept was messed up. I felt like a person getting over a stroke, creatively. And I'll tell you, had I known it was going to take so long to begin to feel comfortable again, I might not have picked it up."

He struggled on his own for a few years and finally turned to Bill Green, a highly respected West Coast reed player and teacher, "another Earl Bostic, as far his knowledge of the saxophone. He gave me some wonderful things to work on, which helped me out quite a bit." Even with Green's assistance, Golson did not really feel comfortable on the horn until 1982, when he and Farmer re-formed the Jazztet.

Golson currently is doing less writing for TV except for commercials - Chrysler, Heinz, McDonald's, Chase Manhattan, a public service spot about AIDS. Another recent project is rather more ambitious. This past year, under a grant from the Lila Wallace-Reader's Digest Foundation, he was commissioned to compose a three-movement concerto for string bass and chamber orchestra. The piece, titled Two Faces, incorporates both classical and jazz elements - each movement allows space for improvisation - and is specially designed to exhibit the two musical sides of his soloist, Rufus Reid, a major jazz bassist with solid classical chops. It premiered in May 1992 at New Jersey's William Paterson College, where Reid heads the Jazz Studies and Performance program and where Golson was completing a two-year artist-in-residence stint.

"It's hard to put that kind of excitement into words," says Reid, reflecting on the singular experience of having a concerto written especially for him by a world-class composer. "We all learned how to play a lot of the music from Benny Golson, and here I am getting a chance to actually work with him. And then he's writing a piece with me in mind, which encompasses all the things that I've studied through my career just trying to be a better bass player and musician. So to play a piece like this, it's not only a challenge, but having it written by Benny is really exciting. I can't tell you how fantastic I feel about it. It just puts a little extra pressure on me to play the hell out of this thing" (which, by the way, he did). An original and demanding work for the instrument, Two Faces, Reid maintains, is "definitely going to be a significant contribution to the bass repertoire."

Over the years Golson has made many significant contributions to the jazz repertoire - "Along Came Betty," "Killer Joe," "I Remember Clifford," "Stablemates," "Whisper Not." He is, Art Farmer believes, "one of the most melodic writers that there has been in jazz. His use of harmony to support the melody is so great, and the songs that he writes are such a pleasure to improvise upon. No one makes these songs become standards. They become standards because people like to play them. They live off their own energy. I could use all the adjectives like 'consummate' and 'wonderful' and 'fantastic,' but you're probably using those already." (Of course, they mean a lot more coming from Art Farmer.)

Today Golson deftly balances pen and horn. He plays what could be called a "thinking-musician's hard bop," deliberate and introspective, more cerebral than visceral, but never meek and always swinging. And he is feeling "better than ever" about his playing. "Today, as we speak, I'm having fun, and now I feel that I've regained my forward motion, to some degree. People say, 'Oh, you don't play the way you used to,' and I say, 'Thank you. I don't want to sound like that anymore.'

"Why continue to sound the way I sounded thirty years ago? That's not moving forward. I want to sound the way things are now. When a person sits down to write, or if he's in a situation where he's going to play, he should reflect where he is at that moment. Time should become your confederate. You should lock yourself in tandem with time on its one-way journey, moving ever forward. That's the way creative people should be moving - ever forward into the darkness of the unknown where things are awaiting your discovery. That's the adventure.

"You can play it safe. Everybody can do what you see in the light. But the real hero is the one that delves into the darkness."

* * *

In the fall of 1992 Benny Golson's bass concerto, Two Faces, performed by Rufus Reid, made its New York premiere at Lincoln Center. That concert also marked the world premiere of another of his orchestral compositions, Other Horizons, featuring guest soloist Art Farmer. Moving ever forward, Golson now is working on a symphony.

© Bob Bernotas, 1992; revised 2002. All rights reserved. This article may not be reprinted without the author's permission. This article appears in Reed All About It: Interviews and Master Classes with Jazz's Leading Reed Players (Boptism Music Publishing).

Photo: Carol Steuer